[originally published on October 21, 2015 at www.law-dlc.com]

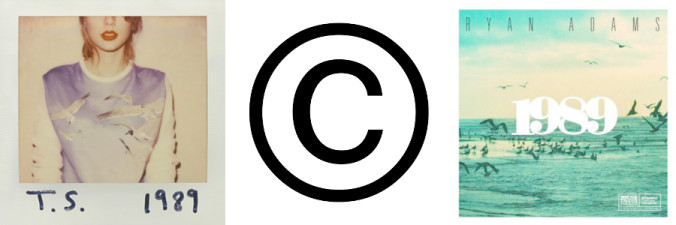

In August, Ryan Adams[1] announced his intentions to release song-by-song and nearly note-for-note cover of Taylor Swift’s “1989” album.[2] He covered every single song and all of the same lyrics, just stripped down and re-recorded as a more guitar-based interpretation.[3] It is a rather audacious project for an artist that is more of an indie musician than a pop star. After the release of his covers album, many people asked me that all-too-common question:

How is that legal? How is that not copyright infringement?

Certainly an artist selling his own version of an entire album of someone else’s popular songs has to run afoul of copyright law, right? If Ryan Adams were to personally profit from Taylor Swift’s songwriting, that feels unseemly, right? Copyright law, however, sees it differently.

Copyright law provides that Taylor Swift has the exclusive right to “prepare derivative works based on the copyrighted work.”[4] These exclusive rights are nevertheless limited in certain ways. When writing and recording “1989,” Taylor Swift created multiple copyrighted works: the lyrics, the sheet music and later the sound recordings themselves. Each of these may be separate copyrighted works.

In this instance, Ryan Adams is not directly covering the sound recordings of Taylor Swift’s “1989” (he is not reproducing or re-transmitting the exact sound recording – his whole intent is to change the sound but keep the lyrics and musical structure). Accordingly, Ryan Adams is not infringing any sound recordings and the limitations on exclusive rights in sound recordings (17 U.S.C. § 114) is not at issue for this covers album. Whereas the use of lyrics and song structure does concern Ms. Swift’s rights.

Copyright Law and Compulsory Licenses

Pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 115, U.S. copyright law allows for a “compulsory license” to make and distribute new sound recordings of copyrighted nondramatic musical works. The statute makes this clear: “When phonorecords of a nondramatic musical work have been distributed to the public in the United States under the authority of the copyright owner, any other person, including those who make phonorecords or digital phonorecord deliveries, may, by complying with the provisions of this section, obtain a compulsory license to make and distribute phonorecords of the work.”[5] Naturally, this compulsory license requires a few procedural hurdles to clear, yet none of them required Ryan Adams or his record company to directly obtain Taylor Swift’s permission. He needed only to provide Swift notice of his intent to make a covers album.[6]

What does this compulsory license require of Ryan Adams? Quite simply it only requires him to “not change the basic melody or fundamental character”[7] of Taylor Swift’s songs, i.e., do not change the lyrics or make the songs unrecognizable.

Subsequently, after publishing and distributing his own version of her songs, Ryan Adams only owes Taylor Swift a royalty – a fixed amount that is based on the sales of his own product. It should not surprise you to know that the amount of this royalty is painfully trivial, too. It might be less than ten cents per song per sale. (“With respect to each work embodied in the phonorecord, the royalty shall be either two and three-fourths cents, or one-half of one cent per minute of playing time or fraction thereof, whichever amount is larger.”[8])

Anyone can get a compulsory license? I am going to be the next rock star!

Copyrights and YouTube Video Covers

Now that we know about the availability of compulsory licenses, we can all go re-record Taylor Swift’s “1989.” We can then upload our mind-blowing cover versions to YouTube and become internet famous. And it will only cost us pennies! What a great investment. Or, maybe not entirely. For copyright law is quirky and (as noted above) distinguishes between the copyright in the song from the copyright in any audiovisual recording. For the “compulsory license” Ryan Adams gets would not automatically extend to him making a music video or any video clip using songs written by another. This requires an additional license, more commonly known as a “sync” or “synchronization” license – as your YouTube cover is both an audio work and a visual work that combines multiple copyrighted uses.

Yes, your YouTube cover may technically be an infringement. I have a YouTube channel where I have tried to cover a few songs on guitar.[9] No, it is not going to make me famous. And yet I might be a dirty, no-good copyright infringer, too. For YouTube is not in the business of determining what is or is not copyrighted or potentially-infringing. If an artist or songwriter complains that your cover song is infringing, YouTube is likely going to remove the video clip first and ask questions later. YouTube does not mess around with the DMCA.[10] For YouTube does not want to risk being vicariously liable for copyright infringement. Because Prince will most definitely sue you for using the sound recording of his song in your video, even if your kid is super cute dancing to it.[11]

But what do we do about this sync license? Fortunately, YouTube has made the effort to acquire licenses from various music publishers, as stated by the Harry Fox Agency.[12] Accordingly, in most cases, YouTube has acquired the necessary video+ song+audio license on your behalf. How nice of YouTube. The problem, if any, is that the list of songs actually licensed to YouTube is not readily available. There is no searchable database of licensed songs. If you intend to generate revenue from your sublime and heart-wrenching cover of “Every Rose Has Its Thorn” – you probably need to contact BMI or ASCAP to ascertain whether the correct licenses are in place.[13] Many artists and bands do encourage covers of their songs as they see the benefit in the indirect exposure to their music. It is just not a universal position by musicians, which requires your compliance with existing copyrights and licenses.

Now if you will excuse me, I need to go practice my power chords and work on my acoustic version of “Enter Sandman.” It might break YouTube from all the attention! I just need to make sure it is properly licensed first.

[1] Ryan – the American, not Bryan the Canadian.

[4] 17 U.S.C. § 106(2).

[5] 17 U.S.C. § 115(a)(1).

[6] 17 U.S.C. § 115(b)(1).

[7] 17 U.S.C. § 115(a)(2).

[8] 17 U.S.C. § 115(c)(2).

[10] Digital Millennium Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §§ 512, 1201.

[11] See Lenz v. Universal Music Corp., 2015 U.S. App. LEXIS 16308 (9th Cir. Sept. 14, 2015).

Recent Comments