On December 29, 2016, music group Run-DMC, an inductee of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame™, filed a lawsuit against online retailer Amazon.com, big box store Wal-Mart, and a series of manufacturing entities and suppliers.[1] Run-DMC claims to own a registered trademark, in addition to other intellectual property that the lawsuit asserts has generated over $100,000,000 since the 1980s. Run-DMC alleges that Amazon and Wal-Mart are liable for trademark infringement and trademark dilution. It seeks a permanent injunction and monetary damages of $50,000,000.

How did Amazon and Wal-Mart find themselves at the center of a high-profile trademark infringement action against one of the most iconic and influential musical groups of the modern era? Is this mere oversight or a concerted effort to trade on the goodwill of the RUN-DMC brand? Similarly, how is Amazon liable if it merely allowed a third-party entity to offer a product through its site?

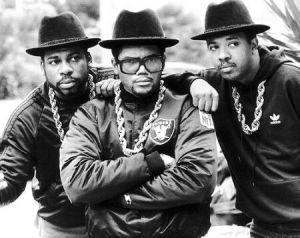

The Run-DMC Trademark(s)

Without putting too fine a point on it, the Run-DMC logo trademark is one of the most iconic images in American pop culture.

(ironically, this above image is currently found on Amazon’s website. It even includes the trademark signifier on the logo!)

In 2004, Run-DMC filed an application to register its trademark rights. Run-DMC has since acquired a federal registration with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for both the word and design of the RUN-DMC mark and logo.[2] Why it took over twenty years for the group to seek federal trademark protection baffles me, but it is secondary to this analysis, as it had common law trademark rights in New York dating back to the 1980s.

Run-DMC also claims rights in certain style of glasses (“Cazal” glasses) which its members commonly wore and promoted in association with its music performances:

The lawsuit includes as Exhibits examples of Amazon offering for sale t-shirts with the Run-DMC logo in addition to the stylized Cazal glasses (even identifying them as “RUN DMC Style Glasses” on the site).[3] Amazon even offers for sale a full Run-DMC costume incorporating these trademark images and logos.[4] As I have previously discussed, costumes can incorporate elements of protectable intellectual property and are not automatically public domain. It can be an infringement if not properly licensed.

Enforcing the RUN-DMC Trademarks

Run-DMC is the owner of the RUN-DMC trademarks at issue, both at common law and covered by the federal registration. Run-DMC’s common law rights may be restricted to those areas of geographic use (primarily New York), but its federal registration extends trademark protection throughout the United States.

Trademark Infringement Claims

Run-DMC has sued Amazon and Wal-Mart for federal trademark infringement under the Lanham Act, 34 U.S.C. §§ 1051-1127. This is based on the allegation that Amazon and Wal-Mart are using the RUN-DMC word and logo in association with the manufacture, promotion, distribution and offers for sale of clothing and related items that are commonly associated with Run-DMC, the music group. Apparently, Amazon and Wal-Mart do not have a license from Run-DMC to sell these products. Oops.

The Lawsuit also includes allegations of common law trademark infringement and unfair competition, based on New York state law. For the most part, these claims overlap with the federal trademark allegations (and remedies for infringement), but lawyers correctly include these additional causes of action for completeness and consistency.

Trademark Dilution Claims

The interesting part of this case regards the purported fame of the trademarks. Given the profile of the band and the continued recognition of these marks in commerce, the average person would likely determine that these marks rise to the level of being “famous” marks as well. Run-DMC has sued on grounds of “dilution” of its marks under federal law in accordance with the Federal Trademark Dilution Act,[5] codified in part at 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c). Claims for dilution or tarnishment of a famous mark can bring damages in the form of injunctions and monetary damages – even if there is no likelihood of confusion or evidence of actual economic injuries.[6]

Pursuant to federal law, a mark is “famous” if “it is widely recognized by the general consuming public of the United States as a designation of source of the goods or services of the mark’s owner.” There are a series of factors that assist in determining fame-worthiness. Notably, just because a trademark owner is famous does not make all of his/her marks famous. Ask Lady Gaga about that little quirk sometime.

With regard to “fame,” this case presents another interesting twist. While am I not licensed there, and I do not practice in New York, the Lawsuit contends that New York state law (via an opinion from the Second Circuit federal court) does not require evidence of “fame” to protect against the dilution of a trademark.[7] Accordingly, even if the judge or jury determines that the RUN-DMC logo or related imagery is somehow no longer famous under the Lanham Act, New York state law may still grant heightened protection against blurring, tarnishment, or dilution of that same mark. In practice, this makes for a lower evidentiary threshold for the Plaintiff and provides a larger hurdle for the Defendant to overcome in any dilution claims.

Did Amazon and Wal-Mart Infringe?

As of today, neither Amazon nor Wal-Mart have filed an Answer or other response to the Lawsuit. Most likely, the first filing will be a Motion to Dismiss for various reasons. Even if they do eventually file an Answer, it will essentially just deny the allegations without explanation. This is standard operating procedure at this stage of a litigation matter.

The question will be how Run-DMC asserts that Amazon and Wal-Mart are liable. There are multiple ways to be liable for trademark infringement. Direct infringers are obvious and often easy to prove. There is also “secondary liability” for trademark infringement that can expose someone like Amazon or Wal-Mart if they vicariously profit from another’s infringement or if they indirectly contribute or induce a third-party to infringe a trademark. The tests for such secondary liability are different from direct infringement, too.

Vicarious liability is typically established through the party’s relationship with a direct infringer. Such vicarious liability can be established when the indirect party (i.e. Amazon/Wal-Mart) has the right and ability to control the actions of the direct infringer. Additionally, in this context, Run-DMC would need to demonstrate that Amazon/Wal-Mart derive a direct financial benefit from the specific direct infringement. In these instances, upon proof of such a relationship, Amazon/Wal-Mart can be held strictly liable for the acts of the direct infringer, similar to the relationship between an employer and employee, when an employee commits a tort while in the scope of his employment.[8]

Contributory infringement differs in that Run-DMC would need to demonstrate that (1) the Defendant(s) know of the infringement; and (2) the Defendant(s) materially contribute to or induced the infringement. This requires a more active role by the alleged secondary infringer. Amazon and Wal-Mart would have to overtly encourage and contribute to the infringement. Of course, providing unlimited access to the infringing products through popular online/brick-and-mortar retail stores that are commonly frequented by millions of customers would certainly be a colorable claim for “encouraging” or “inducing” the infringing acts.

At this point, I cannot offer much more than guesswork as to how this case will proceed. The facts, as alleged, do not paint a pretty picture of the Defendants. I am curious to see how the Defendants respond to Run-DMC’s various allegations. For trademark infringement is rarely obvious at first glance. Okay, sometimes it is, but those cases are rare.

[1] RUN-DMC Brand, LLC v. Amazon.com, Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., Jet.com Inc., et al., Civ. No. 1:16-cv-10011, United States Southern District Court of New York (December 29, 2016) (“the Lawsuit”).

[2] U.S. Trademark Reg. No. 3310249 (October 16, 2007).

[3] Exhibit “B” to the Lawsuit.

[4] Exhibit “B” to the Lawsuit.

[5] It is now essentially rolled over into the Trademark Dilution Revision Act of 2006 (TDRA).

[6] 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c) (“…regardless of the presence or absence of actual or likely confusion, of competition, or of actual economic injury.”)

[7] Lawsuit at ¶ 62 (citing Starbucks Corp. v. Wolfe’s Borough Coffee, Inc., 588 F.3d 97, 114 (2d Cir. 2009)).

[8] Commonly known as the doctrine of respondeat superior.

Recent Comments