Last night, the Los Angeles Rams and the New England Patriots played Super Bowl LIII. It was one of the worst exhibitions of professional football in a long time, and certainly the most boring Super Bowl to date. Enough people will be writing about that game today, but I see it as an opportunity to further discuss the NFL’s SUPER BOWL® trademark. And this is why:

The NFL is a known trademark bully. Someone should petition to cancel its SUPER BOWL® trademark registration. And I think I have found a way for this petition to be successful. The NFL fraudulently acquired the registration and it should be canceled.

Brief history of the SUPER BOWL trademark

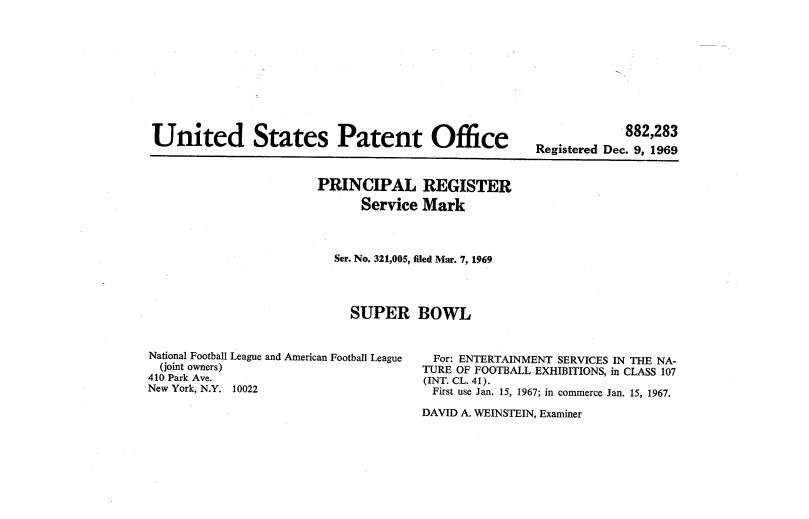

The term “Super Bowl” has been used to identify the NFL’s annual championship game for fifty years now. The NFL acquired a federal trademark registration for SUPER BOWL® in December 1969, and has been aggressively enforcing these trademark rights ever since. There is no doubt that it is a well-known and valuable trademark. Meanwhile, I wrote an article about potential defenses to the NFL’s trademark claims a few years ago and explored in detail the merits of nominative fair use of trademarks. As part of my research, I went back through the application history for this SUPER BOWL trademark and how the NFL acquired it.[1]

This is the registration certificate for the SUPER BOWL® word mark:

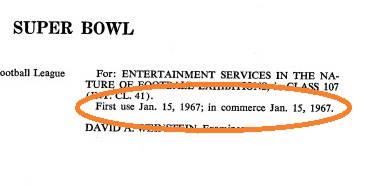

Nothing surprising here, right? It is a standard USPTO trademark certificate of registration that lists the key names, dates, and owners of the mark. Something jumped out at me, however. This:

The origins of the term “Super Bowl” and the NFL’s subsequent adoption of it as a trademark for the NFL-AFL World Championship Game are well-known. The NFL has even commissioned a stand-alone site for the history of the game. But the game itself was not actually called the “Super Bowl” until the 1969 edition of the game, and even then the term was applied retroactively based on Joe Namath’s famous guarantee and subsequent upset by the New York Jets over the favored Baltimore Colts.

The first two “Super Bowls” were not actually called the Super Bowl at the time.

This “date of first use” of January 15, 1967 coincides with the date of what we now refer to as Super Bowl I, but at the time this game was merely called the AFL-NFL World Championship Game. Put more plainly, the SUPER BOWL trademark was not used in commerce by the NFL on January 15, 1967. This stated “date of first use” is a lie.

Fraud on the PTO

Why is this “date of first use” important? It is because the NFL, through its trademark lawyers at the time, knowingly made false representations to the United States Patent and Trademark Office when it applied to register the SUPER BOWL trademark in March 1969. This is fraud.

Recently, in the case of Anello Fence, LLC v.VCA Sons, Inc.,[2] the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey held that a trademark owner’s false declaration of “first use” of 1963 in an application to register a trademark constituted “a knowingly false statement sufficient to cancel” trademark registrations. The Court subsequently cancelled two federal trademark registrations by this decision. While the NFL’s SUPER BOWL® trademark has been registered for almost fifty years and is therefore legally “incontestable,” the fraudulent procurement of a trademark is accordingly a ground for cancellation of both a contestable and incontestable mark.[3]

Of course, the USPTO has maintained heightened standards for proving “fraud” in the context of trademark applications and registrations. For a third party to successfully cancel a registration, the Lanham Act provides that there must be evidence that “the registration was procured by fraud, [and] a showing that must be made by clear and convincing evidence that the applicant or registrant knowingly made a false, material representation with the intent to deceive the PTO.”[4] The Anello Fence court, however, held that a knowingly false declaration of a date of first use may be sufficient to rise to the level of a materially false representation that has the intent to deceive the PTO.

It is indisputable that the NFL’s “first use” of the SUPER BOWL trademark was not January 15, 1967. The actual use of SUPER BOWL came at least two years later, which may seem trivial fifty years later, but trademark law thrives on nuance and such trivialities.

Who can file a Petition to Cancel?

Pursuant to the Lanham Act, to establish standing to petition to cancel a trademark registration, a party must demonstrate that it has a “real interest” in the outcome of the proceeding.[5] This means that the petitioner must have a “direct and personal stake” in the outcome.[6] Essentially, the petitioner must show that it will be damaged by the continued registration. It is a relatively low threshold to meet. This is fair, because trademarks exist to benefit the public. If a trademark owner is committing fraud, it should be punished for its transgressions.

Given that the NFL routinely sues restaurants, churches, and even individuals over uses of the term SUPER BOWL that are knowingly protected by the doctrine of nominative fair use, any of these entities or individuals can plausibly assert damages from being the NFL’s use of the SUPER BOWL® registered trademark as a commercial weapon.

Bullies do not like to get punched back. Someone just needs

the resources, the patience, and the willpower to fight the NFL machine.

[1] See generally U.S. Trademark Reg. No. 882283 (Dec. 9, 1969 registration).

[2] Civ. Action No. 13-3074, 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13894 (D. N.J., January 28, 2019).

[3] 15 U.S.C. §§ 1064(3) and 1065 (the “Lanham Act”).

[4] See Covertech Fabricating, Inc. v. TVM Bldg. Prods., 855 F.3d 163, 174-75 (3d Cir 2017).

[5] Ritchie v. Simpson, 170 F.3d 1092 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

[6] Petroleos Mexicanos v. Intermix S.A., 97 U.S.P.Q.2d 1403 (T.T.A.B. 2010) (quoting Ritchie v. Simpson, 50 USPQ2d at 1027).

Recent Comments