Even in the midst of a pandemic and an unofficial national lockdown, people still have to eat. With outings to the local restaurant and trips to the grocery store being potentially risky, food delivery services have become an essential part of American life in 2020. For large-scale service providers like Grubhub, it has been a relative goldmine for business.

But is Grubhub scamming us all? On May 15, 2020, BuzzFeed reported that even if you seek to bypass Grubhub service fees by calling restaurants directly, you may have been fooled by a bait-and-switch phone number. These restaurants are still paying Grubhub for extra fees.

How is this legal? More specifically, is this a violation of the Lanham Act for false advertising or customer confusion and deception?

What is Grubhub allegedly doing?

According to BuzzFeed and other reports from outlets such as Vice, Grubhub enters into a contractual relationship with a participating restaurant. As part of this partnership of sorts, Grubhub creates a “unique phone number” for that restaurant that appears on all Grubhub platforms (website and apps). When customers call this number, Grubhub automatically re-directs that call to the restaurant itself, but then collects a percentage fee from the restaurant for this service. So far, so good: this seems reasonably fair.

The problem arises when third-party search engines such as Google list phone numbers for the same restaurant when an individual customer searches for it. If you want to help a small business owner and try to contact a restaurant directly to knowingly bypass Grubhub fees, using Google to find the direct phone number seems like the best way to do this. Unfortunately, according to the reports, Grubhub has managed to get Google to list the alternate Grubhub-linked phone number on these search results – even without the Grubhub® name or logo appearing in the results. Even if you do not intend to use Grubhub, the restaurant still ends up paying a fee to Grubhub.

This no longer seems reasonable or fair. It has the stench of unlawful conduct, even fraud.

It also is not limited to Google. It appears based on other independent reporting that Grubhub uses the same potentially-deceptive phone number bait-and-switch on Yelp, which may only list the Grubhub number and not the direct restaurant phone number. Yelp and Grubhub have their own contractual relationship, separate from the contracts each restaurant signs with Grubhub. This is inherently immoral conduct by Grubhub if the reports are true.

But the Grubhub is only taking a small fee, not unlike Peter Gibbons siphoning off fractions of a penny from every Initech accounting transaction… right? Right?!?!? Unfortunately, these fees are not a mundane detail. And just like Peter’s plan, it may be illegal.

Grubhub’s exploitative telephone fees

Many restaurants simply cannot do business without the help of a service like Grubhub. Grubhub assists with expanding advertising and delivery services. Being listed on the Grubhub website and app may be a necessary evil for a restaurant in a local economy.

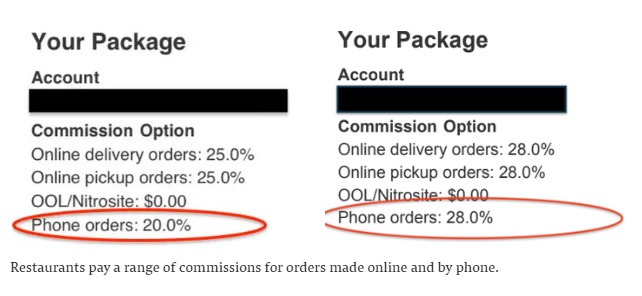

I think we can all agree that Grubhub should be compensated something for these services generally. As I stated before, that seems reasonably fair. Unfortunately, according to BuzzFeed and individual accounts, Grubhub is taking commission fees as percentages of the entire transaction, often in excess of 20 percent of the total order. This is significant money.

This is soulless and wrong. It is especially exploitative during a pandemic. Twenty percent commission feels wrong even before the Google/Yelp alternate number trick is factored in. Making matters worse is that customers have been intentionally trying to avoid using Grubhub and these fees might still be assessed to struggling restaurants.

Thus, the next question is whether there might be legal recourse. As a trademark lawyer, my first instinct is to ask whether there might be implications under the federal Lanham Act.

Is this False Advertising or another violation of the Lanham Act?

The Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125 et seq., is the primarily known as the trademark statute, but it is much broader than trademarks. Courts have specifically held that the Lanham Act “goes beyond trademark protection.”[1] It exists to protect businesses from unfair competition, including false advertising and other misleading or deceptive acts in commerce. The actual language of Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act states as follows:

Any person who, on or in connection with any goods or services, or any container for goods, uses in commerce any word, term, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof, or any false designation of origin, false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact, which—

… is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive as to the affiliation, connection, or association of such person with another person, or as to the origin, sponsorship, or approval of his or her goods, services, or commercial activities by another person, or

… in commercial advertising or promotion, misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of his or her or another person’s goods, services, or commercial activities,15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)

shall be liable in a civil action by any person who believes that he or she is or is likely to be damaged by such act.

This is broad statutory language and courts have held that this section of the Lanham Act should be “broadly construed” and that it does concern false representations by those engaged in commerce.[2] By forcing Google and Yelp to list alternative phone numbers that are not actually the restaurant’s direct phone number – and profiting from this conduct – this certainly feels like “false” or “misleading” or deceptive acts that are “likely to cause confusion” in the scope of commercial activities.

If someone were to sue Grubhub for false advertising under Section 43(a), the following elements would need to be proved: (1) a false or misleading statement of fact about a product; (2) such statement either deceived, or had the capacity to deceive a substantial segment of potential consumers; (3) the deception is material, in that it is likely to influence the consumer’s purchasing decision; (4) the product is in interstate commerce; and (5) the plaintiff has been or is likely to be injured as a result of the statement at issue.[3]

Applying the Lanham Act to a hypothetical Grubhub example

In this hypothetical example of a customer seeking to order from a restaurant but intentionally seeking to avoid using Grubhub, each of these elements can be demonstrated. It would be a classic example of false or deceptive advertising that should subject Grubhub to damages or an injunction.

Walking through each of the elements: the customer searches for the restaurant’s phone number on Google, but is given the alternate number that goes through Grubhub first (even though Grubhub is not listed on the Google result). That is at a minimum a misleading statement of fact, if not outright false. Further, this search result is inherently deceptive or has the capacity to deceive this customer by giving the reasonable impression that the Google result is the restaurant’s actual phone number. Third, if the customer is intentionally avoiding Gruhub, the deception is material because it has improperly influenced that decision to the benefit of Grubhub. This would also be damaging to the customer because of the failed desire to avoid Grubhub from the outset. This is false advertising under the law.

There is just one problem, however.

Individual customers generally do not have standing to sue under the Lanham Act. The Supreme Court has held that even if an individual customer is deceived and injured, there is no legal standing because that injury is not a “commercial” injury suffered by a direct or indirect competitor.[4]

Thus, Grubhub’s Lanham Act exposure is only to direct or indirect competitors. Essentially, an individual restaurant owner would have to be the party to bring a lawsuit. The good news is that same elements would apply. If customers are deceived by the alternate phone numbers that re-direct through Grubhub and cost the restaurant 20% of more of a total sale, that could rise to the level of a deceptive commercial activity that causes economy injury and damages.

Is there any real legal recourse for customers and restaurant owners?

Of course, any hypothetical restaurant owner in this scenario has other problems at the moment. Keeping a small business running is hard enough in good times, but the coronavirus situation has added to the degree of difficulty. Begrudgingly accepting Grubhub’s alternate phone number tricks with Google and Yelp as a “cost of doing business” may be deemed a necessary evil just to keep the phones ringing and orders being placed. Even if the restaurant owner had the financial resources and time to pursue legal recourse, the cost-benefit analysis is not favorable. Litigation is expensive and lengthy. Results are never guaranteed and Grubhub has the resources to outspend any small business owner on lawyers and litigation costs. Not even a clear-cut example of false advertising under the Lanham Act would be an “easy” win for any individual litigant.

The good news is that some government entities are taking action to stop or at least slow down these questionable business tactics. According to the Vice article, New York City has recently passed a bill to ban third-parties (i.e. Grubhub) from charging fees for phone calls that do not end in actual sales. Additionally, state Attorneys General may be motivated to investigate these type of deceptive practices given the widespread customer outrage in response to the BuzzFeed article. The Federal Trade Commission may also investigate Grubhub for these same practices. That is the good news. If nothing else, it is a start.

The bad news is that any financial recourse for downstream customers or individual restaurant owners is likely to be minimal. To the extent Grubhub is one day enjoined from using alternate numbers and charging commission fees for the service, the legal system moves slow. Grubhub and others in the industry will likely have found new ways to charge usurious fees.

I do not enthusiastically welcome these food delivery

overlords, but at the same time I acknowledge the logistical problems that

would exist without them. I just wish they could exercise some degree of morality in the process.

[1] Schlotzsky’s, Ltd. v. Sterling Purchasing & Nat’l Distrib. Co., 520 F.3d 393, 399 (5th Cir. 2008).

[2] Id. (citing Seven-Up Co. v. Coca-Cola Co., 86 F.3d 1379, 1383 (5th Cir. 1996)).

[3] Taquino v. Teledyne Monarch Rubber, 893 F.2d 1488, 1500 (5th Cir. 1990).

[4] Lexmark v. Static Control Components, 134 S. Ct. 1377 (U.S. 2014).

Recent Comments