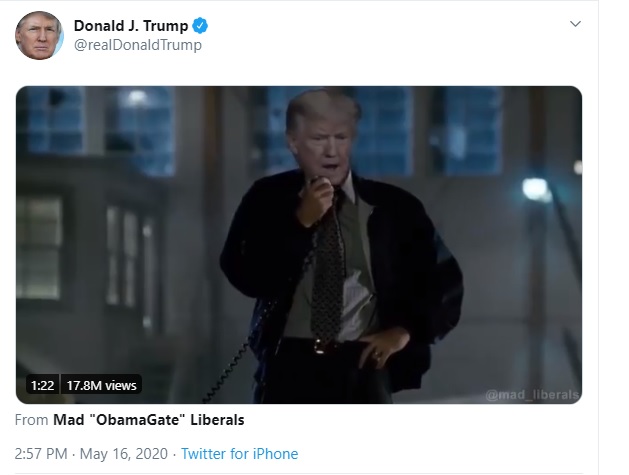

On Saturday evening, May 16, 2020, Donald Trump shared a cartoonish deepfake video to his Twitter account. Trump’s 80 million followers saw an edited video of the famous speech from the 1996 movie “Independence Day,” only with the faces of the characters being edited to reflect certain individuals in politics and pop culture, namely with Trump’s face superimposed over Bill Pullman’s face (but not his voice).

While this predictably led to outrage from various corners of the internet, including from Bill Pullman himself, the most common complaint seemed to be “isn’t this copyright infringement?” The answer to this question, as always, is: well, maybe.

Trump is unlikely to have acquired permission to use this clip from Disney[1], including any right to create or share derivative works,[2] but whether or not Trump’s uses constitute copyright infringement is not an easy answer. Copyright is not absolute. There are always defenses to allegations of infringement. Trump could assert the defense of fair use, specifically the right to use the work as part of a parody – which the Supreme Court has held is a fair use of copyright.

If this use is considered a parody, legal precedent holds that Trump did not infringe any copyrights. What if Trump’s use is instead considered satire? Yes, there is a difference between “parody” and “satire” and these distinctions are significant in a copyright fair use analysis.

Copyright and Fair Use

I have written many articles on the fair use factors as they apply to copyright law, most recently with regard to Prince and his concert videos on YouTube. The factors have not changed in over 40 years, but every claim of fair use is to be assessed on its own merits. No two cases are alike.

The fair use factors are to be considered in totality. An accused infringer does not need to satisfy all four factors to gain safe harbor under copyright law, but a copyright owner does not need to prove the non-existence of all four factors to acquire a finding of infringement either. It is a sliding scale of sorts that is weighted by surrounding circumstances. The factors are broadly written for a reason, and are as follows:[3]

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

17 U.S.C. 107

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Application of the fair use factors (in general)

Generally speaking, Trump’s use of “Independence Day” as the framework of a deepfake video was to address the coronavirus and his administration’s handling of the pandemic.

Thus, the purpose and character of the use was not to compete with “Independence Day” moviemakers. Trump’s video edit is unabashedly a derivative work of the original movie clip. But the use was not necessarily for commercial purposes as it is unlikely it is of a nature that would generate revenue for Trump or his administration. Moreover, the question may be whether Trump’s edits to the original and the overall character of the derivative work is sufficiently “transformative” by adding something new to the work that rises above the original. I will address this in more detail shortly when I address the parameters of the parody defense.

The nature of the work factor focuses on the type of underlying work that is at issue. Works of scholarship and information may be more likely to be fairly used as compared to creative works designed for entertainment purposes. A Hollywood movie certainly skews more towards the latter than the former.

The third factor considers the amount of the underlying work used. Trump obviously did not edit or use the entire two-hour movie, but he did use an entire speech from a discrete scene from the movie. It was not a trivial use or even a truncated use of the speech. There are no fixed guidelines for what is considered “fair” but fractional uses tend to be given more lenience than wholesale lifting. Trump’s use of an entire speech (including the unaltered audio) does not weigh in his favor in this analysis.

The last factor is often a catch-all, as it addresses the “market value” of the underlying work. I doubt that Trump’s use of the movie clip will affect the commercial value of “Independence Day.” If anything it might give it more attention and a boost to any downstream financial markets given the circumstances.

Those are the fair use factors generally speaking. To the extent Trump would claim that his use is fair use because of parody that is an even more specific defense that has a large body of law supporting such a claim.

Parody v. Satire

To the extent Trump could assert that his use was “parody” that is almost universally protected as fair use under existing copyright law. On the other hand, if Trump merely claims that his use of the movie clip is “satire,” he may be exposed to a more stringent infringement analysis. Satire is often not afforded protection by fair use. What is the difference between parody and satire?

Parody is defined as “a literary or musical work in which the style of an author or work is closely imitated for comic effect or in ridicule.” Whereas satire is defined as “the use of humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other topical issues.” On its face, this analysis just became interesting because Trump’s purpose for using the “Independence Day” clip sure sounds more like satire than parody, right? Remember that each case is judged on its own merits though. The line between parody and satire can be very blurry, especially in a court of law. This does not even factor in whether satire is dead.

The Supreme Court weighed in on this specific issue in 1994, in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.[4] Yes, a substantial body of copyright law is based on a 2 Live Crew song that used the famous guitar riff from Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman.” The world works in mysterious ways sometimes. In that case, the Court held that the 2 Live Crew song was a parody because it “reasonably could be perceived as commenting on the original [Oh, Pretty Woman] or criticizing it, to some degree.” The Court found that the parody version was able to “provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, create a new one.”

The Supreme Court’s fundamental ruling was that “[p]arody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s (or collective victims’) imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing.” As you can see, this complicates the analysis as there are no bright-line rules and the guidelines are fuzzy at best.

In our example here, Trump’s use of the “Independence Day” speech would fail to generate the necessary thrust if he did not use the underlying copyrighted work as part of his commentary. Trump could arguably assert that his tweet is commenting on the nature of Hollywood politics through its use of inspirational speeches in movies and comparing that to his personal treatment by media and criticizing it by implication.

That did not really help: can you give me a better example?

Common examples of legally allowed (fair use) parody beyond the 2 Live Crew song include Saturday Night Live skits, the movie “Spaceballs” (commenting on Star Wars), and for a more obscure example – the infamous photograph of a pregnant Demi Moore being parodied by Leslie Nielsen. There was even a case about this one.[5]

An example of satire that was not granted fair use protections as works of parody? A book about the O.J. Simpson murders that was written in the style of Dr. Seuss.[6] There was a court case about that one, too. Judges and juries are human; if you disgust them, your claims for fair use are less likely to be given the benefit of the doubt.

Here’s a brain teaser for you though: the works of Weird Al Yankovic. Are they satire or parody? Colloquially speaking, his music is considered “parody” but they may be “satire” in the most classic sense. Weird Al is a smart guy and he knows it is better to be safe than sorry when dealing with copyright law. He always gets a license first, just in case. Whereas in the 2 Live Crew case, they tried to get a license but were denied, leading to the Supreme Court decision.

Conclusions?

The short answer is: it is really hard to give a confident answer on what is or is not parody when considering “fair use” of copyrighted works. The line between parody and satire is thin. It is a perpetual grey area that is best not litigated unless you have a good reason to test the waters.

What about Trump’s use of “Independence Day” for his viral tweet? My gut instinct is that this is a classic example of satire – he used the copyrighted work to make pointed comments on certain individuals in politics and to make a larger point about the state of the nation, with no real need to comment on the movie “Independence Day” or make fun of it in the process. That is just my personal opinion. As you can see, however, it is not hard to make arguments in Trump’s favor that he’s commenting on “Independence Day” indirectly as a rebuke of Hollywood presidents and the American way of life. A judge or jury could agree with that perspective and it would not be unreasonable.

Copyright law is not easy. Every case is fact intensive and

determined on what may seem like trivial details or legal quirks. Of course, if

it were easy, everyone would be a copyright lawyer and it would not be nearly

as interesting! (But seriously, call me first before you try to imitate Donald Trump

on matters like this…)

[1] Disney recently acquired the rights to 21st Century Fox, and is now the owner of the copyright to the movie.

[2] See also 17 U.S.C. § 106.

[3] 17 U.S.C. § 107

[4] 510 U.S. 569 (1994).

[5] Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures Corp., 137 F.3d 109 (2d Cir. 1998).

[6] Dr. Seuss Enters., L.P. v. Penguin Books USA, Inc., 109 F.3d 1394 (9th Cir. 1997).

Recent Comments